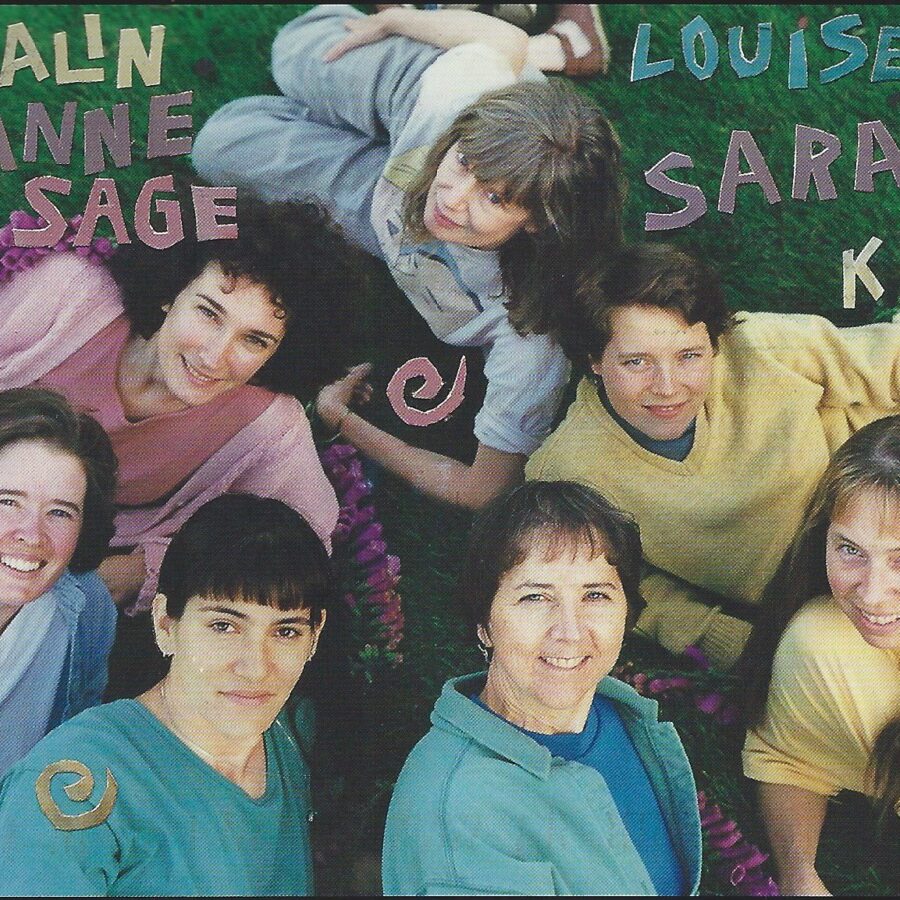

In a relatively short span of 20 years, from 1983 to 2003, Louise Rae Williams produced a nearly unprecedented volume of work. She sold, traded, and donated over 200 finished works to various public and private collections. Her total output in these two decades included over 1,000 individual pieces using various mediums, sizes and shapes. She averaged more than two exhibitions a year including 18 solo exhibitions and 27 two person and invitational exhibitions. She influenced thousands of art students while teaching at four colleges and from her studio. She accomplished her work by mastering a wide variety of mediums and techniques including oils, pastels, watercolors, print making, and mixed media using almost anything at hand as her canvas.

Louise was a western artist as most of her work was envisioned and completed in the western United States and remain in private and public collections in western states. She was born and lived in the west her entire life. But by no means did Louise fit the stereotypical description of a western artist of the Remington-Clymer romantic tradition nor of the Georgia O’Keefe western naturalist school. Rather Louise drew images of the contemporary western experiences and especially the impact of the western macho culture’s impact on women, wives, children and the environment. Her west included the alienated, angels, bird boys, victims of the Green River serial murderer, dead cows, children dreaming, the mentally ill hallucinating, family, erotic cloudscapes and the sensuality of existing. She made the west bigger and deeper than Remington’s representative vignettes and her control and use of color and light compare with those of Georgia O’Keefe.

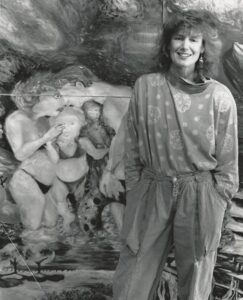

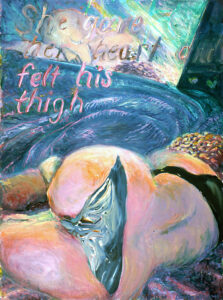

“While at graduate school in the early 1980’s I began to explore images of night such as dreams, romantic and parental love. These “Night Dramas” were two distinct bodies of work. The largest were expressionistic images of figures in beds on 5’x9’ paper executed in charcoal with pastel. These drawings portrayed profound experiences that usually occur on beds: birth, sex, reading to a child, sickness, dreaming, death. The second series was executed in vibrantly colored pastels on 30”x40” black paper. These images were of the more public night dramas occurring at parties and lounges. As I was also painting in oils, one huge painting called “Cul de Sac” (8’x16’) was an attempt to, in one painting, to “summarize” everything I wanted to express. Not surprisingly, a kernel of expressive need led to more paintings and drawings.” From her artist statement for her 2003 retrospective.

“While at graduate school in the early 1980’s I began to explore images of night such as dreams, romantic and parental love. These “Night Dramas” were two distinct bodies of work. The largest were expressionistic images of figures in beds on 5’x9’ paper executed in charcoal with pastel. These drawings portrayed profound experiences that usually occur on beds: birth, sex, reading to a child, sickness, dreaming, death. The second series was executed in vibrantly colored pastels on 30”x40” black paper. These images were of the more public night dramas occurring at parties and lounges. As I was also painting in oils, one huge painting called “Cul de Sac” (8’x16’) was an attempt to, in one painting, to “summarize” everything I wanted to express. Not surprisingly, a kernel of expressive need led to more paintings and drawings.” From her artist statement for her 2003 retrospective. “Intensely painting images of women, birth and mothering: A REAL FOCUS ON THE MADONA. Voices speak: rasping in the images religious, physical and Freudian symbolism borne with the relationship of mother to child. A sentimental obsession with babies obfuscated by questioning. I paint triplets (several sets), an old woman with quints dolls, a hostage with her baby, a girl baby being diapered by young boys and a birth. In supermarts dewy soft infants abound. I paint, I wonder why there? The answers, as often is true, questions—hope, rebirth, beauty, love? Visions of life’s continuity, the vulnerable infant self within, society’s (my) hope for the future and the blessed innocence of purity ooze out with the paint.”

“Intensely painting images of women, birth and mothering: A REAL FOCUS ON THE MADONA. Voices speak: rasping in the images religious, physical and Freudian symbolism borne with the relationship of mother to child. A sentimental obsession with babies obfuscated by questioning. I paint triplets (several sets), an old woman with quints dolls, a hostage with her baby, a girl baby being diapered by young boys and a birth. In supermarts dewy soft infants abound. I paint, I wonder why there? The answers, as often is true, questions—hope, rebirth, beauty, love? Visions of life’s continuity, the vulnerable infant self within, society’s (my) hope for the future and the blessed innocence of purity ooze out with the paint.” “Depression consumes me as the time for my residency at the Ucross Foundation nears (due to Sara’s death). This time has been self-assigned for mourning Sara’s loss in my work. How does an artist, how does one reconcile the outrageous, heinous act? Wyoming. Stepping off a small jet in Sheridan. The sky lifts. A boundless blue is hoisted by red hillocks with nipples. My studio begins to fill with dark and lurid images: visions of death, my denial and anger. Occasional exoduses into the Wyoming skyscape are a relief. A cow dies, falling in a ditch and lays rotting.”

“Depression consumes me as the time for my residency at the Ucross Foundation nears (due to Sara’s death). This time has been self-assigned for mourning Sara’s loss in my work. How does an artist, how does one reconcile the outrageous, heinous act? Wyoming. Stepping off a small jet in Sheridan. The sky lifts. A boundless blue is hoisted by red hillocks with nipples. My studio begins to fill with dark and lurid images: visions of death, my denial and anger. Occasional exoduses into the Wyoming skyscape are a relief. A cow dies, falling in a ditch and lays rotting.”

“There is no question that Louise Williams’ is a political engaged art. She is deeply concerned with humans suffering and outraged at injustice and barbarism…She is deeply concerned about women, children, family and community, and she works this caring into her pieces without forgetting that they are visual art and must communicate through the processes of the media. Perhaps because her thematic works seem to evolve gradually from her personal life – the African Series grew from the visit to Egypt, a country both African and Middle-eastern – her paintings, while socially engaged, are not particularly didactic or scolding. They also carry a readable, communicable statement, which is not always the case with art that mixes the intensely personal with moralizing messages.” From Art Access, April 1995.

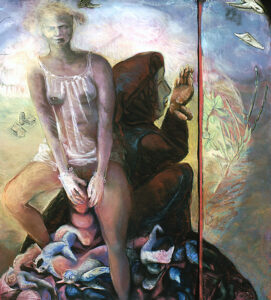

“There is no question that Louise Williams’ is a political engaged art. She is deeply concerned with humans suffering and outraged at injustice and barbarism…She is deeply concerned about women, children, family and community, and she works this caring into her pieces without forgetting that they are visual art and must communicate through the processes of the media. Perhaps because her thematic works seem to evolve gradually from her personal life – the African Series grew from the visit to Egypt, a country both African and Middle-eastern – her paintings, while socially engaged, are not particularly didactic or scolding. They also carry a readable, communicable statement, which is not always the case with art that mixes the intensely personal with moralizing messages.” From Art Access, April 1995. “Women are creating in every kind of traditional and avant-garde art form. The role of female art in the return to realism and figurative art is well recognized. My work grows from the figurative expression of Alice Neel, Max Beckman and the social awareness of Kathie Kollwitz. I’m the beneficiary of feminism that brought a re-examination of subject matter of mother/child, female eroticism, children and male/female relationships. There is an attempt to address the important issues in our society perhaps only by expressing their horrific, humorous, sometimes lovely and always ubiquitous complexity, but moreover in the process of doing my work I find gratitude for the dance we all seem to share in common.”

“Women are creating in every kind of traditional and avant-garde art form. The role of female art in the return to realism and figurative art is well recognized. My work grows from the figurative expression of Alice Neel, Max Beckman and the social awareness of Kathie Kollwitz. I’m the beneficiary of feminism that brought a re-examination of subject matter of mother/child, female eroticism, children and male/female relationships. There is an attempt to address the important issues in our society perhaps only by expressing their horrific, humorous, sometimes lovely and always ubiquitous complexity, but moreover in the process of doing my work I find gratitude for the dance we all seem to share in common.”

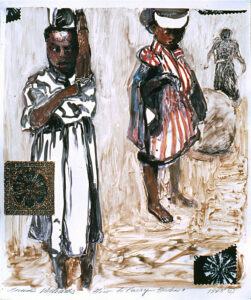

“The paintings in the “African Series” are drawn almost entirely from two newspaper photographs of different sets of reunited sisters, orphaned in the conflicts in Somalia and Rwanda. In these works, Williams suggests that it is the images of children, themselves that are the “angels” and there is no longer a need to draw in symbolic or fantastic figures. The subject matter of the pictures carries its own resolution and the paintings can now support a more abstract style.

“The paintings in the “African Series” are drawn almost entirely from two newspaper photographs of different sets of reunited sisters, orphaned in the conflicts in Somalia and Rwanda. In these works, Williams suggests that it is the images of children, themselves that are the “angels” and there is no longer a need to draw in symbolic or fantastic figures. The subject matter of the pictures carries its own resolution and the paintings can now support a more abstract style.

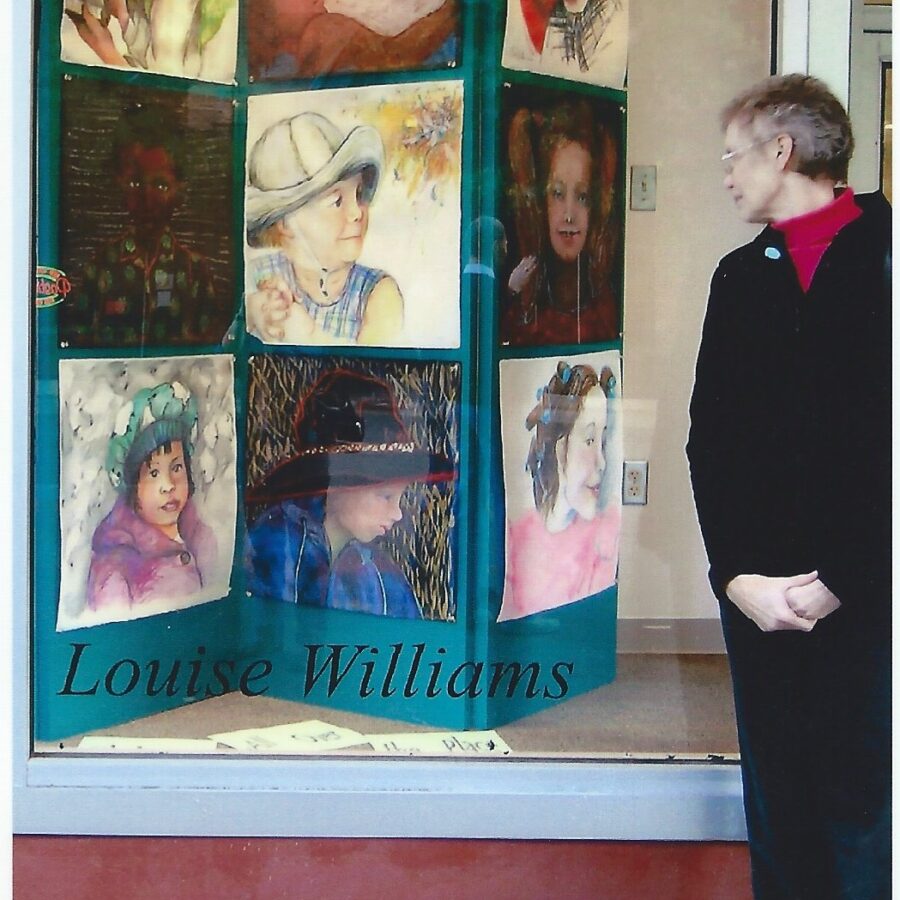

“Innocence and beauty, the commerce of our society and its use of images of children. Behind a barrage of historic and current imagery of children as sweet and cuddly is our hope for ourselves and the future. Most don’t dwell on the future that for some children holds the biological diseases of mental illness. The roulette wheel spins some into unpleasant futures. It is a humanizing experience to remember that the homeless mentally ill and “weird” neighbors who pace and talk to themselves were once beloved, if they were lucky, and innocent children. To see the children deserving of care and love in the dirty, smelly, drunk and hallucinating adult means that we must address the systematic and personal failures that encourage the treatment of the street, the mess of services most counties Washington provide.

“Innocence and beauty, the commerce of our society and its use of images of children. Behind a barrage of historic and current imagery of children as sweet and cuddly is our hope for ourselves and the future. Most don’t dwell on the future that for some children holds the biological diseases of mental illness. The roulette wheel spins some into unpleasant futures. It is a humanizing experience to remember that the homeless mentally ill and “weird” neighbors who pace and talk to themselves were once beloved, if they were lucky, and innocent children. To see the children deserving of care and love in the dirty, smelly, drunk and hallucinating adult means that we must address the systematic and personal failures that encourage the treatment of the street, the mess of services most counties Washington provide. “One constant source of imagery throughout my career has been the mother-child relationship. At times most of my work has drawn on this imagery. Years ago, after viewing my slides an interviewer asked, “How many children do you have?” My paintings and drawings of family relationships, particularly the mother-child relationship were informed by historical Christian images of the holy family. In a more “modern” interpretation, I sought the spiritual in divergent family forms. Thus, the iconography was of airplanes not angels (although angels in retribution continue to fly into my imagery) electric current instead of a halo, TV’s stuffed toys, pajamas with feet, blue herons in the background.”

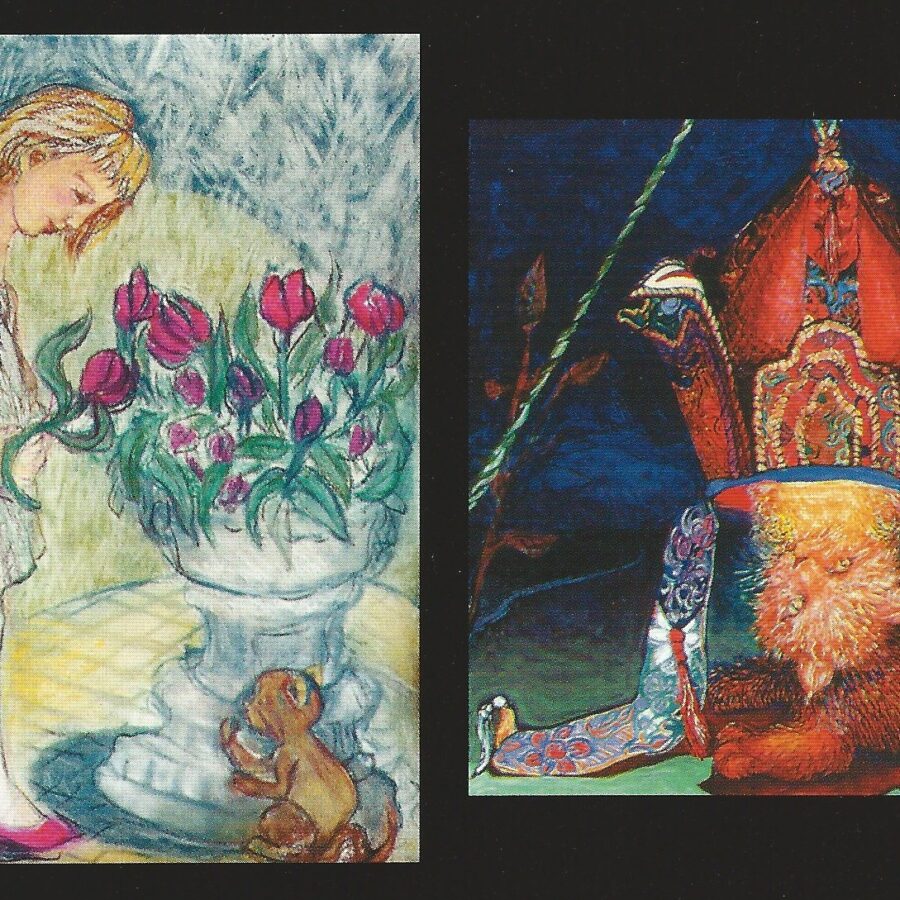

“One constant source of imagery throughout my career has been the mother-child relationship. At times most of my work has drawn on this imagery. Years ago, after viewing my slides an interviewer asked, “How many children do you have?” My paintings and drawings of family relationships, particularly the mother-child relationship were informed by historical Christian images of the holy family. In a more “modern” interpretation, I sought the spiritual in divergent family forms. Thus, the iconography was of airplanes not angels (although angels in retribution continue to fly into my imagery) electric current instead of a halo, TV’s stuffed toys, pajamas with feet, blue herons in the background.” “These new paintings have evolved from pastel and acrylic paintings of children in recent exhibits. The evolution was been a more complex imagery that includes animals, adults and more natural forms. I am excited about the return to the oil painting medium after a long hiatus, and the further development of mixed media gouache paintings on black paper. Both media are layered with translucent glazes of color to create mysterious and symbolic light within the paintings.”

“These new paintings have evolved from pastel and acrylic paintings of children in recent exhibits. The evolution was been a more complex imagery that includes animals, adults and more natural forms. I am excited about the return to the oil painting medium after a long hiatus, and the further development of mixed media gouache paintings on black paper. Both media are layered with translucent glazes of color to create mysterious and symbolic light within the paintings.”